The kindergartners at St. Louis’s KIPP Wisdom Academy stood with their hands apart and palms up, facing a whiteboard festooned with rows of vowels and consonants.

Their teacher, Sonya Taylor, was leading a lesson designed to help them recognize sound and letter patterns. In a piping, resonant voice — she stretches it out Sundays as a singer and worship leader at her church — Taylor called out a string of words for the class to echo, clapping simultaneously, before repeating the sound they had in common.

“Say ‘rub, tribe, scrub’!”

“RUB, TRIBE, SCRUB!”

“What’s the end sound?” she trilled in syncopated eighth-notes.

“Buh-Buh-Buh,” answered all 20 students, sounding like a school of fish.

The lesson comes from the Heggerty curriculum of phonemic tutorials, one of four reading-specific programs in use at KIPP Wisdom. Taylor’s class, along with their schoolmates in grades 1–4, are taught for hours each week how to pick apart the phonics code through a sequence of clapping, call-and-response, group discussion and independent study. The aim is to identify which letter combinations produce certain sounds and, with enough practice, to get a successful start on reading.

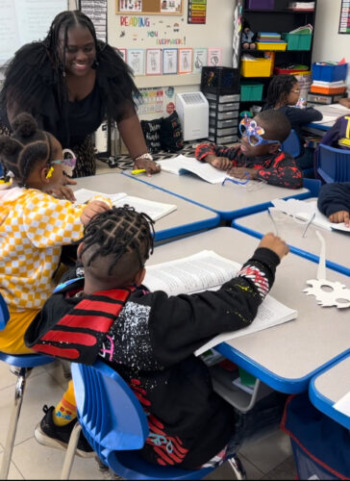

As states launch a raft of new literacy laws, the charter network is rolling out more testing and training in schools nationwide.

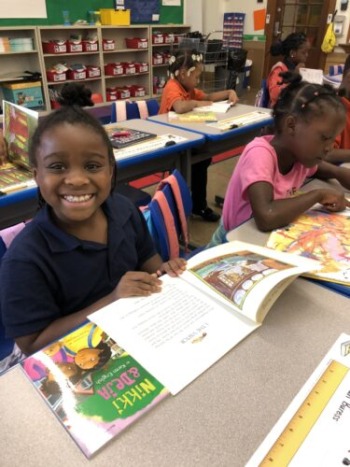

Courtesy of KIPP St. Louis

One analysis found that St. Louis’s KIPP Victory saw the highest reading growth on state testing of any elementary school in Missouri.

As in dozens of other states over the last decade, Missouri lawmakers recently mandated that students between kindergarten and the third grade be screened for reading challenges. It’s part of a widespread campaign among educators and activists to bring English language arts into closer alignment with the “science of reading,” the sprawling body of psychological and neuroscientific research exploring how people come to understand the written word. And in Missouri, where reading scores ranked around the middle of the pack nationally even before the pandemic, school leaders hope the new regime of testing and additional support will help kids recover from substantial learning loss suffered over the last few years.

Kim Stuckey is president of the Missouri chapter of the Reading League, an organization dedicated to spreading awareness of the science of reading. In an email, she called the state’s actions a positive step, while cautioning that more substance is needed to change how teaching candidates are trained around literacy.“Building teacher knowledge is critical to transforming reading outcomes for all children,” Stuckey wrote in an email. “That said, teacher preparation programs need to align their coursework with science-of-reading research so that everyone is moving in the same direction.”

KIPP St. Louis, which operates six schools throughout the city, executed its own turn to the science of reading even before the change in law. The largest charter management organization in the United States, enrolling roughly 120,000 students across nearly 300 campuses, KIPP is completing a gradual overhaul of its literacy instruction, which will take effect for all of its schools by 2025. Over the last few years, that revision has brought new curricula, training and focus to a local network that was already seeing some impressive results: According to research from Saint Louis University’s Policy Research in Missouri Education Center, KIPP Victory Academy (Wisdom’s sister school) posted the best scores for reading growth of any elementary school on Missouri’s 2021 state standardized testing.

Victory’s principal, Cetera Altepeter, said that KIPP leaders in St. Louis were eager to change their approach, in part because they felt local students “weren’t mastering” the building blocks of literacy.

“We knew that we needed to explore other things and make sure we were staying up on the science and the research,” Altepeter said. “Now we’re starting to see the impact.”

‘There was no strategy for them’

“I don’t think we’re doing this correctly. There has to be a better way.”

Angela Jackson, regional head of elementary literacy instruction

KIPP has long been one of the most well-known and respected names within the charter sector. The network’s rapid spread was fueled by tens of millions of dollars in federal grants, awarded largely in recognition of its success raising the achievement of disadvantaged kids.

The evidence of that success mounted over the last decade, with a 2023 study from the research group Mathematica showing that attending both a KIPP middle and high school made students more likely to attend and graduate from college.But within the organization, some believed they could improve upon their work in foundational literacy. Chief Schools Officer Jim Manly, who previously served for eight years as the superintendent of KIPP’s schools in New York City, remembered that when he was hired in 2014, a kind of agnosticism prevailed on elementary reading strategy — perhaps because KIPP’s national network begin in a middle school.

“One of the things I found when I got there was that they didn’t really have a point of view about early literacy and teaching kids to read, at least in New York City,” Manly said.

At the same time, galvanized by media accounts of nationwide failure to lift reading scores or fully prepare new teachers to impart reading knowledge, states like Mississippi, Nevada, and Michigan began revamping their laws to require evidence-based practices in the classroom and new resources for schools and teachers.

KIPP made its own move in 2019, piloting a series of measures in New York City designed to improve both instruction and professional capacity. Incoming students were tested on reading performance using the DIBELS assessment, with struggling readers assigned to additional reading intervention blocks and elementary reading staff encouraged to take LETRS, an intensive training on literacy acquisition.

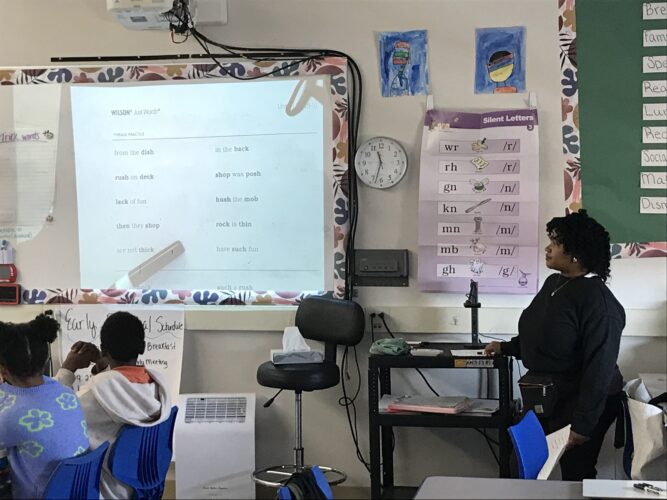

Kevin Mahnken

KIPP schools in St. Louis have moved away from the “guided reading” materials used previously.

Even as COVID disrupted the work of schools around the country, the changes road-tested in New York were brought to six more of KIPP’s 27 regions in the 2020–21 school year, followed by an additional seven in 2021–22. By 2024–25, all 27 regions will have adopted the early literacy agenda.

KIPP St. Louis was one of one of the first regions to opt into the initiative. For years, KIPP Victory and KIPP Wisdom (a third elementary school, KIPP Wonder, was opened in 2019) relied heavily on the “guided reading” technique, through which pupils are taught strategies — such as using context clues or looking for pictures — to determine the meaning of unfamiliar words. Angela Jackson, the region’s head of elementary literacy instruction, said that doubts were building about the effectiveness of those methods.

“We knew that when kids get to longer texts, pictures go away, and there was actually no strategy for them,” recalled Jackson, who worked as a second- and fourth-grade teacher at KIPP Victory before taking her current job. “There were voices around the buildings: ‘I don’t think we’re doing this correctly. There has to be a better way.’”

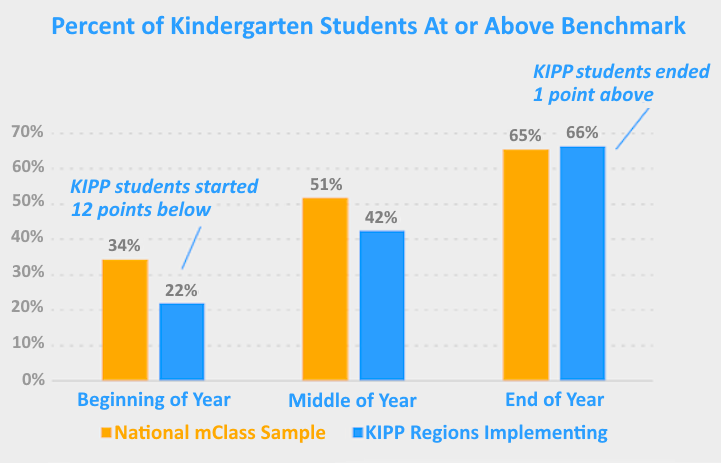

Whether the new way will prove to be the better way remains to be seen. But data from system-wide mCLASS assessments (a literacy screening test administered throughout the academic year) offer some early signs of progress. In a sampling of students from 12 KIPP regions in the beginning stages of implementing the network’s early literacy program, just 22 percent were meeting or exceeding grade-level benchmarks at the beginning of the 2022–23 school year. By the end of that year, 66 percent were — equivalent to the national mCLASS sample.

Kelly Haywood said she has seen some of the same promising early returns in St. Louis. The mother of two daughters at St. Louis’s KIPP Wonder Academy, she has visited and observed Heggerty sessions in her daughter Londyn’s kindergarten class. While reading together at home, the two use some of the same methods to make sense of unfamiliar vocabulary.

“She picks up on those strategies they use in school,” Haywood said. “I’ll ask her, ‘What does this say?’ and if she doesn’t know the word, we’ll sound it out. That has really helped with both of them.”

Reading’s role in learning recovery

KIPP St. Louis’s course correction has now been underway since the early stages of the pandemic, and while substantial changes have already been achieved, much more work remains.

Teachers at KIPP Wisdom and Victory are currently employing parts of four different reading programs. While each brings its own strengths, using such a broad array of materials comes with the risk of teacher burnout.

“We are identifying kids who are at risk … we’re doing something about it.”

Angela Jackson, regional head of elementary literacy instruction

In the coming years, Jackson hopes to streamline by moving all three KIPP elementary schools toward the Core Knowledge Language Arts curriculum, which places a heavy emphasis on the explicit teaching of academic content and the cultivation of students’ subject-matter knowledge. A study released last year showed that schools relying on the Core Knowledge sequence saw large improvements in ELA, math, and science scores.

LETRS training will also be made available to new teachers joining KIPP schools in St. Louis, Jackson added, with stipends available for those choosing to take the course in their off-hours. Roughly 70 percent of elementary literacy teachers in the region have already absorbed the first LETRS volume, which includes about 80 hours worth of sessions on phonics and decoding.

One of them is Erica Williams, who teaches third graders. A St. Louis native and a gregarious personality in the hallways of KIPP Wisdom, Williams came to the profession by an unconventional route: Over a decade ago, concerned over her young son falling behind on reading and developmental milestones, she began volunteering in his Head Start program. After that experience led her to experiment with substitute-teaching, Williams eventually became a lead teacher in her own classroom and earned a master’s degree.

Literacy training in her preparation program was “pretty surface-level,” Williams recalled, with little emphasis on the mechanics of sound and word formation. By contrast, she said, her experience with LETRS opened her eyes to the “ever-involving” process of how young brains develop.

“I’m doing it to become more effective as a teacher,” Williams said. “I’m intrigued by it, and I also see the need.”

Courtesy of KIPP St. Louis

Reading instructor Erica Williams says she has taken LETRS training “to become more effective as a teacher.”

The need, particularly after the COVID era, is greater than ever. In spite of the impressive growth statistics flagged by Saint Louis University researchers, only 49 percent of KIPP Victory’s third and fourth graders demonstrated basic literacy skills on Missouri’s 2023 round of state standardized tests. Far beyond St. Louis, one of the most troubled school districts in the country, Missouri’s reading scores on the 2022 NAEP exam plummeted to their lowest level in decades.

In response, Missouri’s legislature has adopted an initiative called Read, Lead, Exceed, which mandates that schools test their youngest students for reading challenges, develop improvement plans for those that fall behind and regularly communicate with parents on their progress throughout the school year.

Rebecca Treiman, who researches language development at Washington University in St. Louis, called those proposals “good steps.” But she argued that even high-quality training and classroom materials would have a limited impact if teacher turnover in Missouri, which reached new highs during the pandemic, did not abate. Both average and starting teacher salaries in the state are among the lowest in the country, a fact that some have blamed for ongoing churn.

“You might have a trained teacher, but teachers need experience putting this into practice,” Treiman said. “Making sure kids go to school every day, and making sure that teacher salaries are good enough, is really important.”

KIPP St. Louis Executive Director Kelly Garrett applauded the change in policy. He said schools in the network were benefiting from it, while noting that the local affiliate ”started basically putting all our teachers through that a year ahead.”

Jackson said that Missouri’s new laws around student assessment and family outreach would present schools with the challenge of hiring new interventionists to devise personalized action plans and work with parents; with many already operating under a manpower deficit, that task could be significant.

Still, she added, higher standards could ultimately galvanize improvement, both inside and outside the charter sector.

“It’s a lot to take hold of, and it’s going to hold us accountable,” she said. “We are identifying kids who are at risk, we are telling parents that we’re doing something about it, and from that perspective, I think it’s great.”

***

This story was produced by The 74, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on education in America.

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the City Fund provide financial support to KIPP and The 74.