Orchidaceae

Most of the time when we picture orchids, we think of the epiphytic types that grow clinging to the bark and branches of trees and shrubs.

Phalaenopsis, Cattleya, and Dendrobium species are usually epiphytes.

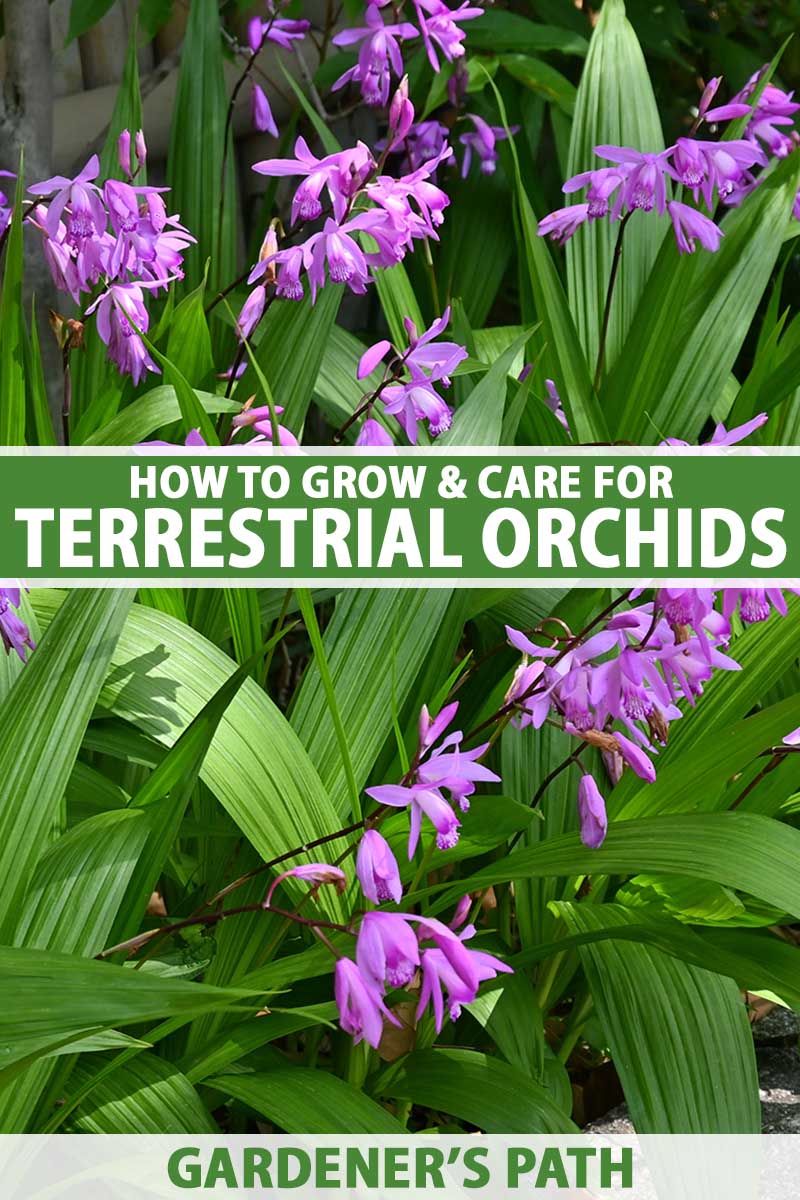

There’s a whole other category of orchids that many of us forget about and those are the ones that grow in soil: terrestrial orchids. These types are special, having specific care needs.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

There are over 200 terrestrial orchid species, providing lots of variety and opportunities to enjoy them in our homes and gardens.

Many of them are every bit as beautiful as those that fill the shelves of stores and stylish hotel lobbies. Plus, many can be grown in the ground as ornamentals, even in locations where the temperatures drop below freezing.

If you’d like to understand more about this group of plants, this guide can help.

Here’s what we will discuss:

Before we jump in, a note of caution. Orchids are so diverse that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to their cultivation and care – and that’s especially true in the case of terrestrial types.

We will give you general growing advice in this guide, but you will need to research the care requirements of the specific species, or, better yet, the cultivar or hybrid that you’re working with.

With that said, most of those that you’ll find on the market can be cared for in a similar way. We’ll discuss all that coming up:

What Are Terrestrial Orchids?

There are three broad groupings of orchids, based on their growth habits: they can be epiphytes or lithophytes, climbers, or terrestrial.

Epiphytes and lithophytes spend their lives attached to trees or rocks, as do climbers, but climbers have rhizomes in the soil below and extremely long stems that spread further than the more compact epiphytes do.

Terrestrial orchids are those that grow in the soil with their roots anchored in the earth.

Epiphytes make up the largest group of orchids that we grow in our homes, while terrestrial types are far less common.

Phalaenopsis, Dendrobium, and Cattleya species are all mostly epiphytes. Actually, most orchid species are epiphytes, with about 70 percent fitting that category.

Terrestrial, or ground orchids as they’re also known, are far less popular with home growers. They are, however, the most common types found growing natively in Europe and North America.

In the wild, these plants can be found as far north as the Arctic Circle and as far south as the southern tip of Patagonia. They grow on every continent except Antarctica, though there are sub-Antarctic species.

They grow in environments as varied as deserts, frozen tundras, and wooded forests.

Some terrestrial species have the ability to adapt to their local environment and become lithophytes, climbing on rocks.

The one thing they all have in common is that they typically grow in the earth and not anchored on other plants or natural structures. They can grow in USDA Hardiness Zones 5 to 12, depending on the species.

Most terrestrial types have what are known as pseudobulbs, which are storage structures that can form below or above ground. Some species have horizontal rhizomes, tubers, or corms, and others have fibrous roots. None of them have aerial roots.

The flowers may be teeny-tiny or massive, and can be pretty much any color except true blue. The same applies to the plant sizes. Some are miniature, just a few inches high, and others can grow several feet tall.

The only thing that unites them is that they grow in the ground.

Cultivation and History

Orchids have been a part of human culture for a very long time.

Cypripedium is a genus of terrestrial orchids found across the Northern Hemisphere that have been used medicinally by native North American people and in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years.

These days, species in this genus are cultivated both as houseplants and garden options, and you can find a variety of different hybrids and cultivars.

Many other species have become important commercially, initially catching on as ornamentals in the early 1800s during the exploration craze of the 1700s and 1800s Age of Enlightenment.

For example, Calanthe orchids were first described by George Rumph (Rumphius) in 1750 using a specimen brought from Indonesia. It was formally named in 1821 by Robert Brown.

Phaius tankervilliae was brought to England in 1778 by plant collector and botanist James Fothergill.

It became known as the first tropical orchid to flower in England when Fothergill’s botanist friends Sarah Hird and Peter Collinson successfully encouraged their specimen to bloom in 1778.

The Ludisia genus was first described in 1818 by English botanist John Bellenden Ker Gawler, though he first called it Goodyera. It was changed in 1825 by French botanist Achille Richard.

The flood kept coming, with Dutch-German botanist Carl Ludwig Blume describing Spathoglottis in 1825, and Bletilla was identified by German botanist Heinrich Gustav Reichenbach in 1853.

Of course, botanists, researchers, and enthusiasts are still discovering new species like Eulophia graminea, which was identified in 2018 in Puerto Rico by Adolfo Rodríguez Velázquez, a graduate student at the University of Puerto Rico.

In their native ranges across the globe, many species are endangered as a result of poaching both for medicinal use and to sell as ornamentals and houseplants. Ludisia, for instance, is hard to find in its native Malaysia because of poaching.

On the other end of the spectrum some, like Arundina graminifolia, have become a little too widespread. This species is considered invasive in Hawaii and is smothering out native plants.

Some species, like Spiranthes sinesis, are described as “weedy,” taking over disturbed areas, fields, and grassy areas in colonies made up of thousands of plants.

Terrestrial Orchid Propagation

Propagating orchids from seed is a daunting proposition, but it’s certainly possible. We have a guide that will talk you through the whole process if this is something you’re interested in.

Dividing existing plants is an easier propagation method or you can purchase a potted plant for transplanting.

From Division

The easiest and most consistent way to produce more plants is to divide an existing specimen. Other methods are less successful for the home grower, so this is the one I recommend.

If the plant is in a pot, remove it. If it’s in the ground, dig it up, digging about a foot down and around the circumference of the plant at least six inches out from the base of the outermost leaves.

Gently brush away as much of the soil or potting medium as you can from around the roots.

Find a natural separation in the plant with both roots and pseudobulbs or stems attached. Tease the plant apart at this point, and use a clean pair of pruners, if needed, to sever the root.

Many terrestrial orchids have a large horizontal root that will need to be cut into sections. Take as many sections as you want so long as each has a stem or pseudobulb attached.

Replant the main plant back in the hole or pot you took it from, filling in around it with soil. Place the division in a new pot or prepared area in the garden.

Transplanting

If you have a potted plant that you want to repot or transplant outdoors, the first step is to prepare the new location.

If you’re using a new container, choose one that is just one size up from the existing container. Fill the bottom quarter or so with an extremely loose, well-draining potting mix.

A product containing a mix of compost, pumice, coconut coir, fine bark, sphagnum moss, and worm castings would be ideal.

That can be hard to find, so look for a potting mix with a majority of those ingredients and add the rest yourself.

De la Tank’s houseplant mix with some fine bark mixed in would be perfect. The final mix should be about a quarter bark.

Pick up some De La Tank’s mix at Arbico Organics in a quart, eight-quart, or 16-quart bag.

If you’re planting in the ground, work in lots of well-rotted compost mixed with bark in a ratio of three parts compost to one part bark.

Dig a hole about the same size as the container the plant is currently growing in.

Plant the orchid in the pot or ground and fill in around it with more soil or potting medium. It should be sitting at the same height it was initially. Water well and add a bit more soil, if necessary.

How to Grow Terrestrial Orchids

What I’ve noticed is that most people start their orchid-growing journey with epiphytic types and become familiar with the needs of these plants, and assume that terrestrial types are the same.

Terrestrial orchids are different. Usually, they need much less frequent watering than the epiphytes, and the top inch or two of soil should be allowed to dry out. Soil retains moisture longer than orchid bark does.

Most have similar light requirements to epiphytes, but not all. Most species need loamy, water-retentive, well-draining soil, but again, not all.

Is all this sounding vague? This is a huge range of plants with vastly variable soil, sun, and moisture preferences.

Understanding the natural environment of the species you’re working with is critical. Ground orchids are found growing natively in sand dunes, mossy bogs, moist forest beds, and everywhere in between, depending on the species.

In my neck of the woods, California lady’s slipper (Cypripedium californium) grows in shady, mineral-heavy seepages and river banks.

In southern Africa, the desert orchid (Eulophia petersii) lives in rocky, sandy soil in full sun.

Species in the Orchis genus grow throughout Europe and south through northwest Africa in tropical rainforests and semi-arid regions.

They grow in environments as wide-ranging as tundras and sandy ocean beaches, which illustrates how important it is to know the needs of the species you want to grow.

The vast majority of terrestrial orchids need consistently moist but not wet soil – of course, with the exception of the desert-dwelling species.

Most terrestrial orchids have deep roots that can stretch a foot or more down, so in general, you need to water deeply but infrequently. Allow the top inch or two of soil to dry out in the garden or the top fifth of the medium to dry out for potted plants.

They generally need rich, loamy potting soil with lots of pumice or other material mixed in to improve drainage and water retention.

Or mix one part bark, two parts sphagnum moss, and one part perlite with a dash of worm castings. Garden soil should be amended with bark and compost, as mentioned above. But there are exceptions.

Most Eulophia species are succulents and need somewhat sandy, rocky, or pumice-heavy soil that should be allowed to almost completely dry out before watering.

Most species want dappled shade, morning light, or bright, indirect light indoors with morning light, but again, check to be sure.

They can usually handle a bit more light than you might expect. But if you want to increase the light, do it gradually over several weeks.

They also like moderate to high humidity. A minimum of about 50 percent is about right for most species.

Don’t fertilize plants in the ground. For those in containers, feed them a 1-1-1 or 2-2-2 (NPK) fertilizer once a month from spring through fall.

Growing Tips

- Know the needs of the specific species you wish to grow.

- Most species require consistently moist soil and dappled or bright, indirect light with direct morning light.

- Well-draining soil is a must.

Maintenance

To tidy up the plant and encourage new blossoms, trim back the flowering stalk once all of the flowers have dropped from the plant. Leave about an inch of stalk behind.

Learn more in our guide to encouraging an orchid to rebloom.

Any branches or stems that are brown, broken, or yellow should be trimmed off. You can also remove any foliage that looks crowded or any stems that are crossing.

When you prune your plant, be sure to use a clean pair of clippers and clean them between plants.

For more details, read our guide to pruning orchids.

You will also need to repot your orchid every few years. As plants age, they need more room to accommodate their new size.

Even if you aren’t going up in pot size, you should replace the potting medium every few years because it will break down, reducing the amount of air reaching the roots.

Our guide to repotting orchids will walk you through the details.

For deciduous types grown outdoors, remove any dead foliage at the end of the growing season. You can also heap some straw or leaf matter over the roots to provide some insulation.

Terrestrial Orchid Species to Select

The best species for you to grow is going to be the one that fits in your environment, so it never hurts to ask local sellers if they have a particular type they’d recommend.

When it comes to good houseplant options, any one of these will work well:

Bamboo

Bamboo orchids (Arundina spp.) have strap-like leaves that resemble grass. The showy, fragrant flowers appear on long stems that are perfect for cutting.

The flowers vary from pink to purple and deep violet. Most contain some amount of white and some even have pure white petals.

Even better, the blossoms appear all year long, though they’re particularly prolific during the spring and fall.

These plants are native to Asia and have become a popular garden option in the Pacific Islands. As heat lovers, they grow best in Zones 10b and up.

While most remain smaller, some species can grow up to six feet tall.

Corduroy

Eulophia species, commonly known as corduroy orchids, inhabit Africa and Asia, where they grow in shady forests.

The leaves are held at the end of fleshy stems and the thin flower spike produces colorful flowers with large sepals and small petals.

They come in the full range of orchid colors, like pure white, yellow, pink, red, purple, and orange.

This genus is popular as a landscaping plant in warm areas like California, Florida, and Hawaii in Zones 9b to 11b.

Most species are succulents that can tolerate some drought, but they prefer sandy soil with regular moisture. While it can vary, most species grow about a foot tall.

Slipper

Even non-orchidists have usually heard of slipper or lady’s slipper orchids (Cypripedium spp.).

These can be found growing natively across the Northern Hemisphere in temperate and subtropical regions.

There are even a few tough species that grow in Alaskan and Siberian tundras. You can find species that will grow in Zones 2 to 10.

The flower stems typically extend well beyond the oblong leaves, and the inflorescence may consist of one single flower or up to a dozen. Colors include pink, purple, yellow, and white.

The often hairy leaves grow from a central stem that emerges from the underground rhizomes.

One of the reasons slipper orchids are so popular is because they’re pretty easy to grow and they can usually tolerate a good amount of shade.

Jewel

Jewel orchids (Ludisia spp.) do have petite, white flowers, but they are mostly appreciated for their pretty foliage.

The rhomboid leaves are typically dark green with some burgundy and have pale vertical stripes.

Did I say pretty? Let me be more clear. The foliage is stunning. The veins of the leaves sparkle in the light like jewels. You honestly won’t even notice the flowers.

These are native to Asia but have found a home in gardens across the globe in the equivalent of Zones 10 and 11.

Ludisia species should be allowed to dry out a little between watering, but the roots should never be allowed to become completely dry.

Most species are low-growing ground covers but some grow up to a foot or so tall.

Nun’s

Nun’s orchids (Phaius tankervilliae) have narrow, pleated leaves and the plants can reach about three feet tall.

Each pseudobulb grows a single stalk of large, colorful, and fragrant blossoms in the winter and early spring. Flowers typically have bronze or brown coloration, along with white, pink, or purple.

This species can tolerate cool temperatures down to just above freezing, but it isn’t a fan of wet roots.

It’s native to islands across the Pacific from Asia to North America, which should tip you off to their temperature tolerance. Grow them outdoors in Zones 9 to 11.

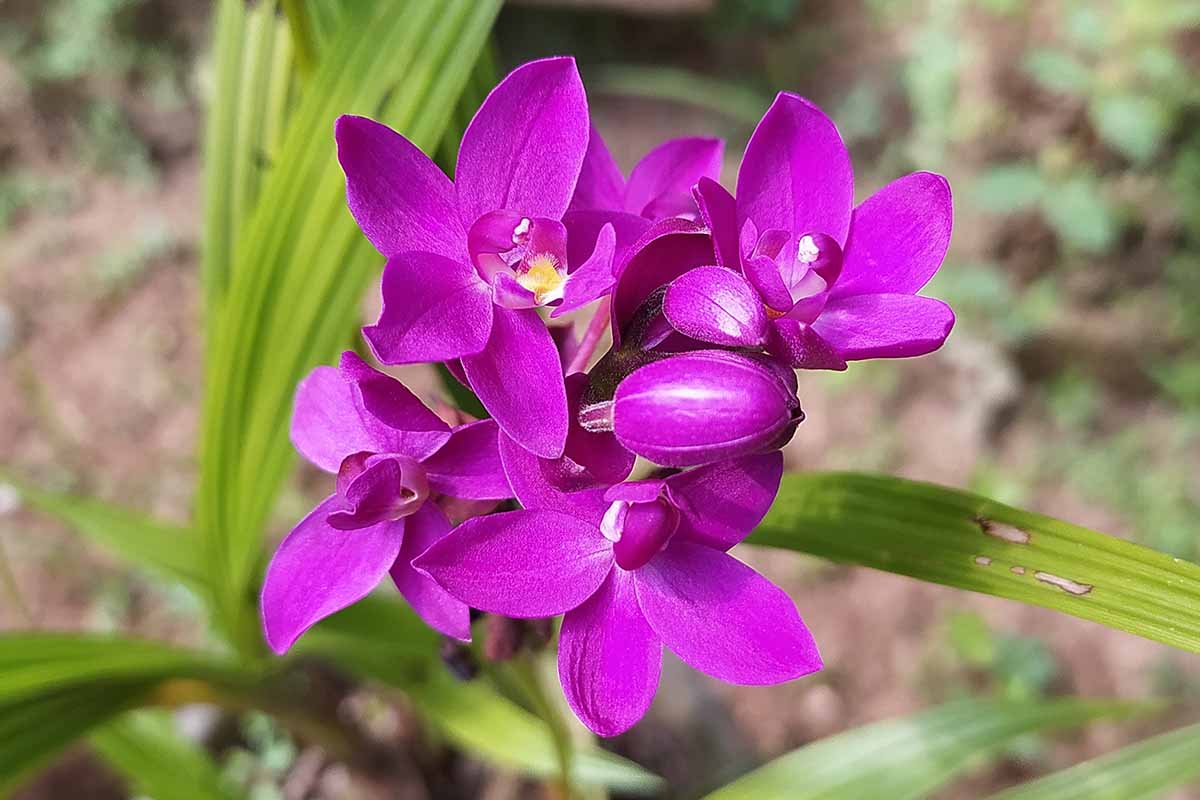

Spathoglottis

Often known as purple orchids (Spathoglottis spp.), these usually have, you guessed it, purple flowers.

The hues can range from pale lavender to deep reddish purple. There are even some with white, yellow, and pink hues and these are – confusingly – referred to as “purple” orchids as well.

S. plicata is the most common species found in cultivation and it always has some purple in the flowers.

They bloom on nearly two-foot-tall stalks with fragrant flowers all year long.

While they can survive freezing temperatures, they really need to be cultivated somewhere that stays above 50°F. Below that, they will go dormant and drop their leaves.

They hail from eastern and southeastern Asia, Australia, and some Pacific Islands and are hardy in Zones 10 and 11.

Urn

Bletilla species are commonly grown as houseplants and outdoors in Zones 5 to 9.

Hailing from across Asia, the long, narrow, pleated leaves emerge from corm-like pseudobulbs that sit at the soil level.

The long flower stalks can reach up to two feet tall and produce cattleya-like flowers in a variety of colors from white to deep purple.

The most common species found in nurseries is B. striata, which is often called “hardy orchid” because it can tolerate temperatures down to 25°F, though the plant will go dormant and lose its leaves once temperatures drop below freezing.

Urn orchids are pretty easygoing, they’ll tolerate drought, overwatering, shade, and sun, to a certain degree.

Managing Pests and Disease

Pests don’t seem to be the biggest problem when growing terrestrial types, but diseases, particularly fungal ones, can be an issue.

Insects

Aphids, mealybugs, scale, and spider mites are all common houseplant pests, and that applies to orchids, too. You might see them on outdoor plants, but much less often.

As a first line of defense, whenever you bring a new plant into your home, isolate and monitor it for a week.

If, despite your efforts, the pests find your plants, a stream of water from the hose once a week can wash the spider mites or aphids off.

Scale and mealybugs can be gently scraped off the plant. Neem oil or insecticidal soap is an effective solution, whether you use it instead of or in addition to the previous methods.

I keep Bonide Insecticidal Soap on hand for just such an event. Find it at Arbico Organics in 16- and 32-ounce spray bottles.

Disease

Viruses can cause unusual patterns and colors on leaves, but there is no cure, so you must either dispose of the plant or learn to live with the funkiness.

Odontoglossum ringspot virus (ORSV) and Cymbidium mosaic virus (CyMV) are the most common.

Spots on the leaves may be caused by bacteria or fungi. Bacteria in the Erwinia and Acidovorax genera cause spotting, as does fungi in the Cercospora genus.

All are spread by splashing water, crowded conditions, and high humidity.

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.) can also cause spotting, often with a tan center.

There’s not much you can do about bacterial leaf spot except remove the symptomatic leaves or take out the plants entirely.

Rot can be caused by fungi, as well, including those in the Pythium and Phytophthora genera.

This can cause black, soft spots on the leaves or roots. Root rot can also be caused by overwatering, which drowns the roots.

To learn more about potential orchid problems, check out our guide.

Best Uses for Terrestrial Orchids

Terrestrial orchids are versatile and diverse. They can grow as potted houseplants or in the garden in borders, as mass plantings, in rock gardens, containers, or to fill shaded areas under trees.

Depending on the species, they can thrive in frigid regions – or they might require tropical conditions, making them better suited for houseplant life.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Terrestrial evergreen or deciduous flower | Flower/Foliage Color: | White, pink, purple, red, yellow, orange, green, brown, bicolored / green |

| Native to: | All regions of the globe except Antarctica | Tolerance: | Some drought, frost (depending on species) |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 2-12 | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Bloom Time: | Summer, spring, fall, winter, depending on species | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Exposure: | Bright, indirect light, morning light, dappled light, full sun to full shade outdoors depending on species | Soil Type: | Typically loamy, rich, airy, some grow in sand |

| Time to Maturity: | 2 years (from seed) | Soil pH: | 5.5-6.5 |

| Spacing: | 1 foot or more depending on species | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | Same depth as container (transplants) | Attracts: | Pollinators |

| Height: | 8 inches to 5 feet | Order: | Asparagales |

| Spread: | Up to 24 inches | Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Aphids, mealybugs, scale, spider mites; Leaf spots, rot, viruses | Genera: | Arundina, Bletillia, Cypripedium, Eulophia, Ludisia, Phaius, Spathoglottis, Spriranthes |

Reach New Levels of Gardening With Ground Orchids

Anyone who has the orchid bug needs to dabble in terrestrial orchids.

The epiphytic types will always hold a special place in our hearts, but until you’ve filled a garden bed or a big, decorative pot with a terrestrial species or two, you haven’t experienced everything these plants have to offer.

Which species is most appealing to you? How will you be growing yours? In a rock garden next to a pond? Or maybe a pot on your kitchen table? Share your plans with us in the comments section below!

And if you’re looking for more information about growing orchids, we have several other guides that might catch your fancy. Check these out: